Idea: The reason some systems support some styles better than others has much to do with the stability of the equilibrium that results from the interaction between the system and the styles of game the players desire (their preferences, or loosely, their creative agenda.)

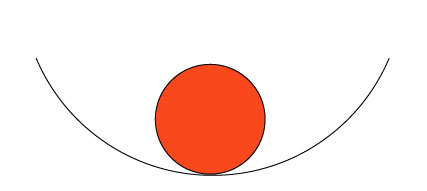

I know, that barely sounded like English. Let’s try a picture. Imagine the course of the game as a red ball. The GM is trying to keep the red session ball placed right at the point that the players enjoy, the place that matches up with their preferences. And the system that you use dictates what sort of surface you’ll find at that point. Imagine that you have 5 players who want to play standard hack and slash dungeoneering D&D with no regard for the story. These players literally make no demands on the game except to have enemies to fight, traps to find, and loot to collect so they can level up and do it again. What sort of surface does that put the ball on?

Think of the horizontal in this picture as representing style. In the middle, we have the style that the group is aiming for. As the ball rolls on this surface away from the center, it will tend to roll right back down to the middle. The D&D system, by virtue of the rewards that are offered (experience, leveling up, stat increases, more feats) will tend to push the game back toward a standard hack and slash dungeoneering style game – even when you deviate from this style. For these players, under these circumstances the D&D system is self-correcting. They’ve found a stable equilibrium between their play style and the system that they use to achieve it.

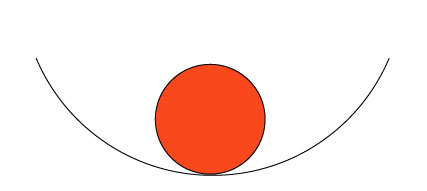

Now consider a group that consists half of people with this style, and half new members that are interested in story or character immersion (or any number of other priorities.) The system still gives us our curve, but now, because the “creative agenda” is different, we’re looking at a different point on that curve. At this point, the system needs to support competing priorities. For some people, running D&D with these priorities works, and of course, based on that, we can’t discount the possibility that they’ve found some sort of equilibrium. In my experience, that equilibrium looks like this:

It is certainly possible to balance the ball on the surface at this point. The problem is what happens when the game deviates from precisely the right place. The ball still rolls downhill, but now, instead of self-correcting, the errors are self-magnifying. Now, the system will tend to push the session away from what the players want rather than back toward it. It’s an unstable equilibrium. The GM can certainly endeavour to push the ball back up the slope (and often successfully at that.) But it takes work (which none of us like, because we’re lazy.) Sometimes that work will require obvious attempts on the part of the GM to achieve this, breaking suspension of disbelief or bringing any number of other gremlins into the picture. And sometimes doing all this work will cause the GM to burn out on the game and give up, ruining the experience for everyone.

I don’t mean to pick on D&D here, but it’s an easy target. The same thing happens with some story games. They work great for the author during playtesting, and then they simply fail for some groups. As people have pointed out, many of these games just don’t work unless you bring the right mindset to the game. Bringing the right mindset is sitting down to play the game with priorities that find a stable equilibrium point on the system curve. The system then keeps you right on the sweet spot. Some groups have trouble ditching their old assumptions about how roleplaying games work when confronted with a new beast. Those old habits put them at an unstable equilibrium point on the system curve, and the result is that the game degenerates into…something else. Certainly not the game as it was intended to be played, and generally not a fun experience. These groups sometimes take away the message that story games suck at producing fun.

To sum up: Some systems work better for certain styles (duh.) For many combinations of system and style, there exists an equilibrium point. The existence of such a point indicates that the desired style can be achieved with that system. The stability of the equilibrium point indicates how difficult the desired style will be to achieve. In unstable equilibrium, the system will tend to push the game away from the desired style when deviations occur. In stable equilibria, the system will tend to push the game back toward the desired style, even when deviations occur.

Posted by karl

Posted by karl